The following is a guest post I originally posted at another instantiation of The Evangelical Calvinist back on August 24, 2009, here.

T.F. Torrance and Union with Christ in Scottish Theology

Without exploring the entire history of Scottish theology as read through the eyes of Torrance, we may note a few key influences on his thinking about union with Christ from this context. Torrance believes that ‘Union with Christ probably had a more important place in [Robert] Leighton’s theology than that given to it in the thought of any other Scottish theologian.’ Torrance gives Leighton (1611-1684) praise for not considering union with Christ simply as a ‘judicial union’ but as a ‘real union’ which occupies the centre of the whole redemptive activity mediated through Christ as saving grace. Utilised in this way union with Christ is fundamentally related to both election in Christ and the concept of saving exchange whereby Christ gives to humanity what is his – his righteousness and filial status – and takes to himself what is not his own – our sin and alienation. In James Fraser of Brea (1639-1698) Torrance identifies the same emphasis placed upon union with Christ, ‘It is through union and communion with [Christ], grounded in the “personal union” of his divine and human natures, that we come out of ourselves and partake of his fullness; we approach him empty to find all our salvation in the all-sufficient Lord Jesus.’ Thomas Boston (1676-1732) viewed union with Christ not merely as a legal union but a ‘real and proper union with ‘the whole Christ’ transformed through his death and resurrection, that is, a union of an ontological kind.’ Boston often spoke of this as a ‘mystical union’ in which all the benefits of the covenant of grace are given to the elect. Torrance traces these ideas back directly through Robert Bruce (c1554-1631), John Knox (1505-1572), John Calvin, and many others.

Of special interest to Torrance is H.R. Mackintosh (1870-1936). Torrance shows how Mackintosh in continuity with Calvin and the Scottish Reformed tradition, also made the concept of the unio mystica central to his soteriology. For Mackintosh, the concept of the unio mystica was merely a dogmatic restatement of the biblically rich material on the believer’s participatio Christi found throughout the New Testament, particularly in the ‘in/with Christ’ language of Paul and in the organic relationship between Christ and believers depicted in Johannine theology.

According to Mackintosh, mystical union effects a change in the believer’s identity. Through participating in Christ there is an ‘importation of another’s personality into him; the life, the will of Christ has taken over what once was in sheer antagonism to it, and replaced the power of sin by the forces of a divine life.’ There is a twofold objectivity about union with Christ: on the one hand, there is a ‘Christ-in-you’ relationship, and on the other there is a ‘you-in-Christ’ aspect. The former has to do with Christ being present within the believer as the source of new life, while the latter points to the foundation of this new life as lying outside of the believer in Christ. The union is mediated by the Holy Spirit. Torrance adopts these two aspects of participation in Christ into his own theology.

Mackintosh was attempting to postulate a union with Christ Jesus that went beyond the merely moral or ethical. Like Torrance, Mackintosh had reservations over using the term ‘mystical union’ (despite teaching its substance), but chose to define what he meant by unio mystica more willingly than discard the term altogether. By ‘mystical’ Mackintosh means, according to Redman, ‘that the believer’s relationship to Christ transcends human relationships and human experiences of solidarity and union.’ In place of a mere moral union Mackintosh presents a spiritual union that, while rational, is beyond human comprehension. By ‘union’ Mackintosh does not mean a complete identification in which Christ and the believer become indistinguishable; this would be an essential union, something found in the writings of some of the medieval mystics. Mackintosh was aware of the risk of pantheism and avoided this in his christology. Through participatio Christi, Mackintosh argues, one has communion with God as a human being because it is through union with the incarnate Christ that we come to commune with God. By defining union with Christ in such a way Mackintosh is in basic agreement with Calvin’s three senses of the term – incarnational, mystical, and spiritual. One can clearly see why Torrance is so attracted to Mackintosh’s theology.

In his critique of Mackintosh’s doctrine of the unio mystica Redman comments on his use of language. He argues that Mackintosh should have ceased using the language of mystical union and instead used concepts more akin to the essential logic of his theology, such as spiritual communion. Torrance perhaps agrees with Redman’s critique for he does not use the term ‘mystical union’ either, but retains the basic three-fold sense of union with Christ. Despite differences of terminology, Torrance considers his use of theōsis, both in terminology and in substance, conforms to a consistent theme of Reformed theology going back to Calvin and found particularly within the Scottish tradition.

Within this very specific trajectory of Reformed theology Torrance posits his own soteriology. Torrance articulates the dimensions of union with Christ in various ways but consistently he sees three realities involved. Firstly, there is union with Christ made possible objectively through the homoousion of the incarnate Son (Calvin’s ‘incarnational union’ ). Secondly, there is the hypostatic union, and its significance for the reconciling exchange wrought by Christ in his life, death, and resurrection (Calvin’s unio mystica). Finally, these two aspects of union with Christ are fulfilled or brought to completion in the communion that exists between believers and the triune God (broadly corresponding to Calvin’s ‘spiritual union’).

In a paraphrase of Torrance’s theology, Hunsinger presents three aspects which correlate approximately to our outline. Firstly, reception, a past event which involves what Christ has done for us. This is received by grace through faith alone. Secondly, participation, a present event, in which believers are clothed with Christ’s righteousness through partaking of Christ by virtue of his vicarious humanity. Thirdly, communion, the future or eschatological aspect which equates to eternal life itself in which believers enjoy communion in reciprocal love and knowledge of the triune God.

According to Torrance, union with Christ is not a ‘judicial union’ but a ‘real union’ which lies at the heart of the whole redemptive activity mediated through Christ as an act of saving grace. Torrance uses three words to elaborate what union with Christ means in his essay ‘The Mystery of the Kingdom’: divine purpose (prothesis), mystery (mystērion), and fellowship/communion (koinōnia). This triadic structure reflects the trinitarian action of the triune God: prothesis – the Father, mystērion – the Son, and koinōnia – the Holy Spirit. Prothesis refers to divine election whereby the Father purposed or ‘set forth’ the union of God and humanity in Jesus Christ. Divine election is a free, sovereign decision, a contingent act of God’s love; as such it is neither arbitrary nor necessary. Torrance thus holds to the Reformed doctrine of unconditional election, one which represents a strictly theonomous way of thinking, from a centre in God and not in ourselves. Torrance draws on certain aspects of Barth’s doctrine of election for he equates the incarnation as the counterpart to the doctrine of election so that ‘the incarnation, therefore, may be regarded as the eternal decision or election of God in his Love…’ Calling upon Calvin’s analogy, Torrance insists that ‘Christ himself is the ‘mirror of election,’ for it takes place in him in such a way that he is the Origin and the End, the Agent and the Substance of election…’

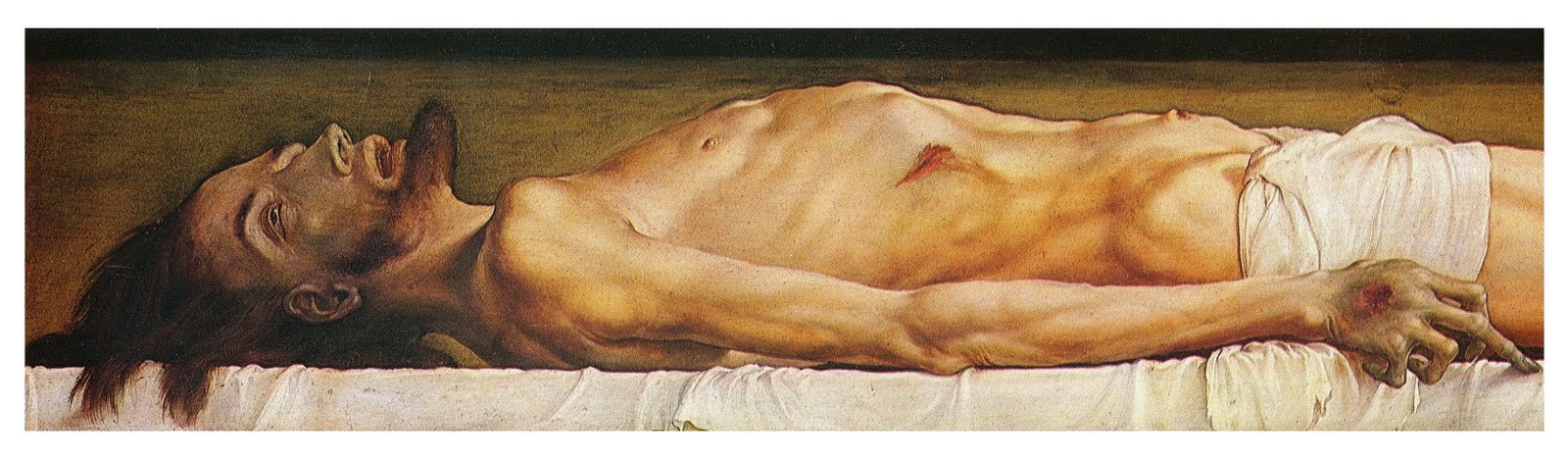

The second key expression Torrance uses is mystērion; the term is applied to Christ, and specifically to the mystery of his hypostatic union. In relation to God this means that the consubstantial union of the Trinity upholds the hypostatic union so that God does not merely come in man but as man. In this union of God and man a complete henosis between the two is effected, and they are ‘perfectly at one’.

He had come, Son of God incarnate as son of man, in order to get to grips with the powers of darkness and defeat them, but he had been sent to do that not through the manipulation of social, political or economic power-structures, but by striking beneath them all into the ontological depths of Israel’s existence where man, and Israel representing all mankind, had become estranged from God, and there within those ontological depths of human being to forge a bond of union and communion between man and God in himself which can never be undone.

Hence the hypostatic union is also a ‘reconciling union’ in which estrangement between God and humanity is bridged, conflict is eradicated, and human nature is ‘brought into perfect sanctifying union with divine nature in Jesus Christ.’

This atoning union is not merely external or juridical but actual, and points to the higher reality of communion. Hence Torrance can assert that:

it is not atonement that constitutes the goal and end of that integrated movement of reconciliation but union with God in and through Jesus Christ in whom our human nature is not only saved, healed and renewed but lifted up to participate in the very light, life and love of the Holy Trinity.Union with Christ must be understood within Torrance’s doctrine of reconciliation to refer to the real participation of believers in the divine nature made possible by the dynamic atoning union of Christ. Torrance contends this is atonement in effect. As a result of the incarnation, humanity is united to divinity in the hypostatic union so that:

In the Church of Christ all who are redeemed through the atoning union embodied in him are made to share in his resurrection and are incorporated into Christ by the power of his Holy Spirit as living members of his Body…Thus it may be said that the ‘objective’ union which we have with Christ through his incarnational assumption of our humanity into himself is ‘subjectively’ actualised in us through his indwelling Spirit, ‘we in Christ’ and ‘Christ in us’ thus complementing and interpenetrating each other.In addition to the hypostatic union Torrance applies the concept of mystērion to the mystery of the one-and-the-many, or Christ and his body the church. Torrance thus understands union with Christ to be largely corporate in nature but applicable to each individual member of his body who is ingrafted into Christ by Baptism and continue to live in union with him as they feed upon his body and blood in Holy Communion. Understanding the church as the body of Christ is thus another way of asserting an ontological union between the community of believers and Christ the Head.

The third term Torrance uses is koinōnia, and it too has a double reference. First, vertically, it represents our participation through the Spirit in the mystery of Christ’s union with us. Second, horizontally, it is applied to our fellowship or communion with one another in the body of Christ. At the intersection of the vertical and horizontal dimensions of koinōnia is the church, the community of believers united to Christ, who is himself united to humanity through the incarnation. Torrance asserts that ‘in and through koinonia the divine prothesis enshrining the eternal mysterion embodies itself horizontally in a community of those who are one with God through the reconciliation of Christ.’ It is this theology of union with Christ by means of fellowship or participation in God which links Torrance’s doctrines of soteriology and ecclesiology; both are aspects of his christology, as we shall see in more detail in the next chapter.

In summarising Torrance’s use of these three concepts Lee’s study helpfully concludes that ‘the cause (causa) of ‘union with Christ’ is prothesis, the election of God. Its substance (materia) is mysterion, the hypostatic union in Jesus Christ, and its fulfilment (effectus) is koinonia, the communion of the Holy Spirit.’ This outline focuses on the trinitarian foundation inherent throughout Torrance’s work which reminds readers not to see the work of reconciliation as exclusively that of the Son, or the Son and the Spirit, but as the work of the triune God.